Chado (茶道), commonly known as Japanese Tea Ceremony, is a discipline focused on the physical and spiritual refinement of the self. Chado touches on many aspects of traditional Japanese culture, from mannerisms to aesthetics, and through Chado, we learn ways to connect more deeply with others.

The word Chado can be translated literally to The Way of Tea. In Japanese tradition, a Way is a lifelong practice whose lessons invariably seep into daily life, turning the practice into a study of living. There are many kinds of Ways, from The Way of Flower Arrangement to The Way of the Sword. In Chado, we learn how to exist in harmony together in the tea room as we share a bowl of matcha.

A Tea Gathering

The purest form of Chado expression is the chaji (茶事), or a tea gathering.

In a canonical chaji, the host invites a small number of guests to their tea room. They first share a meal together, which the host prepares as a celebration of seasonality. The host provides a traditional sweet at the end of the meal, with a design that hints at the theme of the gathering.

During this time, the host prepares the fire by laying charcoal in the hearth. Another term for Chado is Chanoyu (茶の湯), literally Hot Water for Tea, underscoring the importance of preparing a good fire. Without meticulous focus on preparation and fundamentals, the rest of the tea gathering cannot happen.

After the charcoal is laid and hunger is sated, the guests take a stroll through the garden. There, they see further indications of care from their host. The garden has been carefully tidied up while maintaining its wild beauty, and cushions have been placed out for the guests’ enjoyment. They wait outside, enjoying the garden, until the host finishes preparing the tea room.

The host calls the guests back into the room. The scroll on the wall has been replaced with a simple flower vase, and the charcoal has fully lit, announcing its presence with an occasional crackle. The host finally prepares koicha (濃茶), or thick tea, in one bowl for the guests to share.

At the conclusion of koicha, the mood lightens. The host’s assistant removes the blinds from the windows, letting the sunlight in, and the host brings in light sweets for the guests to enjoy. The host replenishes the fire, if necessary, and proceeds to make rounds of usucha (薄茶), or thin tea. The solemn part of the gathering is over; guests drink and laugh, discussing their favorite parts of the day. Once everybody has had their fill, they take their leave, and the chaji concludes.

Spirit of Chado

Dou Gaku Jitsu

Like any Way, the practice of Chado follows three distinct pillars:

- Dou (道), The Way

- Gaku (学), Study

- Jitsu (実), Practice

Dou refers to the spiritual aspect of tea. Fundamentally, tea is the practice of hospitality, and the most important thing we do is serve others. It is crucial to keep this in mind; there is no Chado without the heart.

Gaku refers to the academic aspect of tea. We are lucky to have an abundance of knowledge to draw from, and there is always room to learn more. We say that tea constitutes a lifetime of study; from seasonal motifs to poetry to history, we can always further sharpen our minds.

Jitsu refers to the physical aspect of tea. We train our bodies over and again until the procedures are imprinted onto us. We want to be able to flow from step to step with ease, tea becoming as natural to us as breathing.

In combination, these three pillars form the basis of Chado.

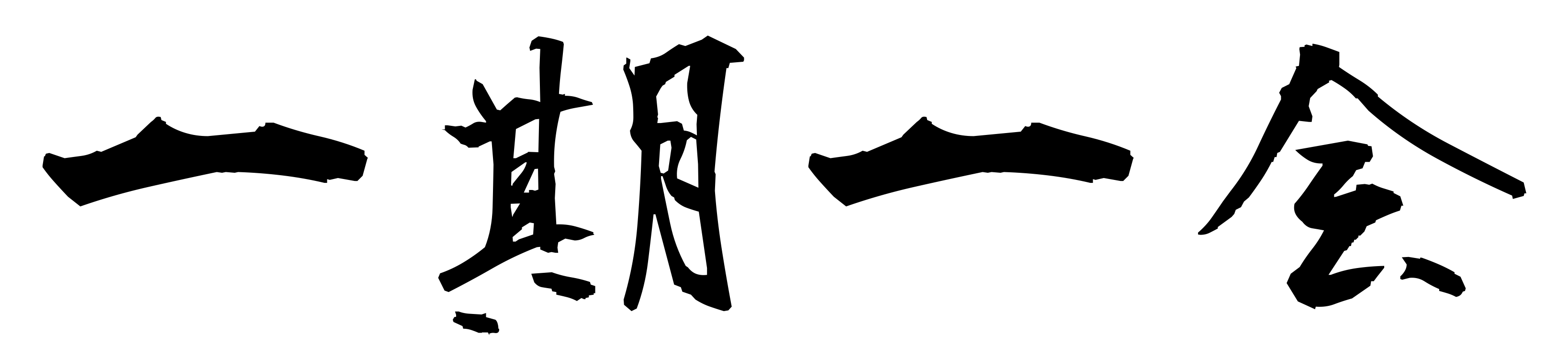

Ichigo, Ichie

A common saying in Chado is Ichigo, ichie (一期一会), or One lifetime, one opportunity.

There is no way to recreate a moment that has already passed; the only thing we can do is be fully present and appreciate when the moment comes to meet us. This comes naturally to many as the seasons come and go. The first lilac blooms are always the sweetest, and the aspens turning the mountains gold in the autumn always draw a crowd.

Chado encourages us to do the same, but in every moment.